If you’ve looked even briefly into the controversial topic of whether or not to consume grains (see my take here), you’ve probably heard of a “better” choice called spelt.

This ancient cousin of wheat has enjoyed rising popularity in health food circles in recent years, especially among those with food sensitivities.

But should spelt be on your grocery list? Is it really healthy?

What Is Spelt?

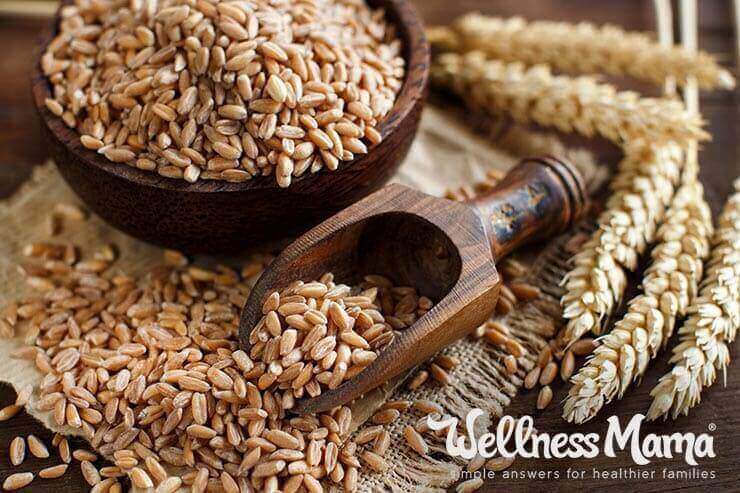

An ancient relative of wheat, spelt originated in the Middle East and gained widespread popularity in Europe as far back as 750-15 B.C. While many grains date back to this time, spelt is still called an “ancient grain” today because it remains largely unchanged even in the last several hundred years, while other forms of wheat have experienced dramatic redefinition.

Over millennia, wheat replaced spelt and other ancient grains as it was cultivated to produce higher yield and free-threshing kernels (to allow the grain to separate easily from the chaff during harvest).

Spelt and other ancient grains are still enjoyed in some parts of the world and have been popularized in the U.S. as a health food. Those who enjoy spelt bread and pasta say it tastes better than wheat and describe it as nutty, wholesome, and more filling.

Spelt can be cooked and eaten whole (called spelt berries) and used as a warm side or in a cold salad, or it can be ground into flour for baking. While most baking sites say that you can substitute spelt for whole wheat flour in most recipes, I find some tinkering is usually needed for the best result, as it contains less gluten and more protein than regular flour.

Wondering what the verdict is? First, the good news:

The Good News: Spelt Is (Slightly) Healthier than Wheat

Many spelt health benefit claims are anecdotal, but there are some reliable studies that indicate spelt has two main advantages over modern wheat hybrids:

Spelt has a Better Nutritional Profile than Common Wheat

While I maintain that grains have little nutritional value in comparison to better food choices like vegetables, spelt does boast a higher protein and mineral content than modern wheat (although some could argue that the difference is slight).

A 2012 study found that:

Spelt differs from wheat in that it has a higher protein content (15.6% for spelt, 14.9% for wheat), higher lipid content (2.5% and 2.1%, respectively), lower insoluble fiber content (9.3% and 11.2%, respectively) and lower total fiber content (10.9% and 14.9%, respectively). There are no important differences in starch, sugar and soluble fiber content, and there is a qualitative diversity at the protein, arabinoxylan and fatty acid levels. (1)

It is important to note that studies also find the nutrient levels vary quite a bit among spelt samples. (2) This means that the strain of spelt used, the environment in which it’s grown, and the method of farming all affect the final product’s nutritional value. So check your labels carefully and choose from credible organic producers.

While spelt is lower in gluten, it does contain gluten. A 1995 study found that the gluten in spelt has largely the same properties as those in wheat and so should be strictly avoided by celiacs. (3)

Anecdotally, many with food allergies do seem to have success digesting spelt. Evidence is lacking as to why. It’s possible that spelt’s greater solubility makes its proteins more digestible, including its gluten. Still, for someone who suspects gluten intolerance or a compromised gut, it’s best to avoid spelt and all grains completely.

But otherwise, here’s another reason to consider spelt:

Spelt Works Well with Sustainable & Organic Farming Practices

I’ve long suspected that food allergies can stem from reactions to the chemicals used in modern agriculture. Today’s wheat crops are one of the worst offenders.

Spelt, since it has not been adapted for modern threshing, has an extremely tough exterior hull that naturally protects the kernel from disease, pests, and mildew. It grows well in wet conditions, extracts fewer nutrients from the soil, and resists rancidity.

This makes it an organic farmer’s best friend and means fewer chemicals passing into the earth and into your family’s food source.

The Not-So-Good News: A Healthier Grain Is Still a Grain

Grains may not be all bad, but the fact is in today’s society overconsumption is all too easy. Highly refined and processed grains are everywhere in the modern American diet. Even products labeled “whole grain” are dubious:

(W)hole grain” refers to any mixture of bran, endosperm and germ in the proportions one would expect to see in an intact grain—yet the grains can be, and usually are, processed so that the three parts are separated and ground before being incorporated into foods. (Refined grains, on the other hand, are grains that have been stripped of their bran and germ.) For a food product to be considered whole grain, the FDA says it must contain at least 51 percent of whole grains by weight. Compared with intact grains, though, processed whole grains often have lower fiber and nutrient levels. (4)

Even when consumed in their true whole form, modern grains have diminished nutritional value compared to years past, and their high levels of phytic acid block nutrient absorption.

Wouldn’t it be better to spend our money, effort, and calories on obtaining fresh produce–vegetables and fruits proven to be brimming with highly available, much needed vitamins, minerals, and enzymes?

But if you must have your bread and pasta, there’s one way to make grains healthier!

Make the Best of It: Sprouting

I’ve talked before about the benefits of traditionally preparing grains, nuts, and seeds to reduce phytic acid and other anti-nutrients. Many studies confirm the nutritional benefit of sprouting grains. It boosts protein content and available amino acids, promotes enzyme activity, and does much of the digestive work your body would otherwise have to do. (5)

If you decide some grains have a place in your family’s meals, consider soaking and sprouting as a way to increase the nutritional value. It isn’t nearly as difficult as you might think. You can use a simple mason jar and a screw-on lid made for sprouting.

Fill the mason jar no more than halfway with organic spelt berries (or grain of choice) and rinse and drain several times in clean, cool water. Fill with filtered water and let it sit overnight.

The next day, drain and rinse, and drain again. Tilt the mouth of the jar (with sprouting lid on) down into a bowl. I just prop the jar up on a folded towel to keep it in place.

Within a day or so, tiny white sprouts will appear. When the sprouts are about ? inch long, they are ready for use. At this point you can dry them in a low oven (125-150 F) or in a dehydrator for about 24 hours. Grind to make flour.

You can also purchase organic sprouted spelt flour from a quality source.

Does spelt have a place in your diet? If yes, how do you use it? I would love to hear!

Leave a Reply